And…. that’s a wrap! This week saw the last workshops that Bristol Clear will run for this academic year. Here is a round-up of what’s been on offer since our launch last October, and what we’ve learned for next year.

Before that, though, we have to say thank you… to you! If you didn’t attend the training, participate in writing retreats, book onto 1:1’s, sign up for mentoring, complete our surveys, or read any of our emails, we’d be finishing the year empty-handed. But because you get involved, we have masses to show for the last year.

Training

We’ve run 36 training sessions across the year and trained 530 people. (that’s over a third of the entire research staff community at Bristol!).

This year’s training was similar to last year’s, covering a range of topics that draws on the full scope of the Researcher Development Framework. Topics like careers, grants, writing & publishing, engagement, policy, communication & impact, research project management and personal effectiveness.

What we did differently this year was release the training schedule further in advance to allow you to sign up earlier. This has encouraged people to plan their training better… so we’ll be doing that again next year.

What we also need to do next year is let you know more about what’s coming up closer to the date. So that you can book on, and take advantage of any drop-outs, if you missed the original call.

Careers drop-in

Careers drop-ins were a new initiative this year, 19 were run across the latter half of the year. These sessions give you space to do your own careers research, check a CV, ask a question, or work on job or grant applications. We make laptops available so that you can explore online careers tools, a growing bank of our own online guidance, books and other resources aimed specifically at postdoctoral career level and a quiet space for you to focus.

These have been growing in popularity, but we think we can do more to advertise them… after all, you told us in CROS that you don’t have time to develop your career outside of your normal daily work – and these drop-ins provide just that opportunity.

Writers Retreats’

A day where you can step out of your norm and focus solely on writing – what a luxury! We saw how much you valued these sessions and so this year upped the number of writers retreats’ to one a month. We ran 9 in total at nearly full capacity each time!

Just think what you could achieve by taking out just one full day a month to write!

1:1’s

75 of you have taken advantage of a half-hour coaching session with one of our staff development officers. These are often about careers decisions. But we’ve also talked about things like prioritising writing, negotiating the authorship position you want on a paper, and planning a tricky conversation with a PI.

Mentoring

In September 2018 we launched the Bristol Clear Mentoring Scheme. We’ve run two cohorts so far (Sept 2018, and March 2019) and created 37 (you tell us ‘high quality’) mentor/mentee matches. The scheme will open to all faculties come September 2019 and we’d expect it to then grow considerably.

Alongside one to one matches, we’ve run Academic journeys events, where academics talk candidly about their own journeys through mentoring. We’ve also run several peer to peer events when staff could practice mentoring with each other and gain the benefits of being mentored by a peer.

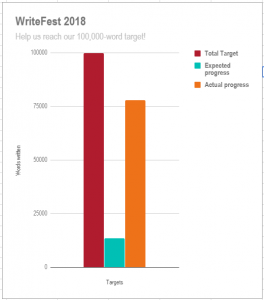

Writefest

In November, we worked with the Bristol Doctoral College to run a month focused on academic writing. Throughout the month there were 3 video shorts containing 9 writing tips, 9 book reviews on how to write books, 5 weeks of activities, 4 drop-in writing days, 4 writing workshops, 3 thesis boot camp days, 3 writer’s retreats and 373,000 (approx) words written! Phew… roll on WriteFest2019!

The Post Doc Residential

In May 2019 we ran a 2-day residential for new postdocs. Those who attended spent two days, away from their everyday work, thinking about questions like: Where have you come from? Where are you heading? What are your values? Why do you do what you do? How can you be as productive as possible, and What do you need to do next?

Feedback was generally very positive, with some good ideas about how to improve the experience. One person found it truly transformative, saying

It was fantastic! I came away completely different, I’ve never had a professional development experience like this, it changed the way I feel about my career. I would like more early career staff to be able to experience this

More Communication:

In addition to these events, we’ve renewed and reshaped some of our communication. We’re now using Twitter (@UoB_Researchers), and have introduced this blog – which has run 35 blog posts through the year. We’ve also introduced the weekly Friday bulletins to keep you all up to date with what’s going on.

And other things:

And then there are lots of other things that we also do that are probably less visible: support the Reps network and the work of the Research Staff Working Party, meet with Heads of School, run the CROS survey, etc.

They are hugely important, though, as they support everything else that we aim to do.

This summer, particularly, we’ll be working on analysing the CROS data, and getting an action plan ready for next year.

And that will also detail our programme for next year, so look out on our webpages and blog for updates on what we’ll be doing for 2019/2020!