(by Dr Bradon Smith, Senior Research Associate, School of Education)

Why write?

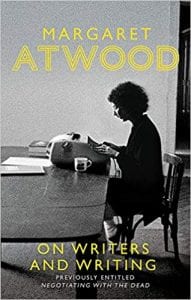

Why do writers write? And what is writing anyway? These are the central questions in Margaret Atwood’s volume of six essays On Writers and Writing, which mixes autobiographical musings with a wide-ranging scholarship on some of the universal themes taken up by writers.

Atwood considers the idea of the writer, and how writers perceive themselves; she discusses the many ways in which writer are interested in doubles, and are themselves somehow their own doppelgänger; she explores the relationship between art and money, and the social responsibility of the writer. She asks, ‘for whom does the writer write?’ and looks at the three-way relationship between the writer, the text, and the reader; and, finally, she delves into the Underworld, and the idea that all writing is, in some way, motivated by a fascination with mortality.

Atwood draws on a dazzling array of examples to illustrate her themes, and the bibliography would make a fascinating reading list. But her writing is eminently readable, quirky, even conversational: “You may find the subject a little peculiar. It is a little peculiar. Writing itself is a little peculiar”. Perhaps this is because these essays started life as lectures (given in Cambridge in 2000); but writing, as Atwood notes, has an apparent permanence – unlike a dance recital (or a lecture) it ‘survives its own performance’.

This erudite, but often light-hearted book won’t help you become a (better) writer, or not at least in any direct way. But it does give rise to some interesting questions for academic writers. Atwood, for example, discusses the difference between a writer, and someone who merely writes. Since anyone can write, what makes a writer? Atwood replies with a macabre metaphor: everyone can dig a hole in a cemetery, but not everyone is a grave digger. For a start, the profession of grave-digger requires stamina and persistence. But the comparison also evokes the character in Hamlet: the grave-digger is a ‘deeply symbolic role’, carrying expectations, fears and superstition. So too with the public role of the writer.

In an amusing list spanning three pages of the Introduction, Atwood lists the reasons for writing given by writers, from the highfalutin (‘To serve Art’) to the bathetic (‘Because I hated the idea of having a job’). So, why do we as academics write? Hopefully, it is to shed light on something. Perhaps here is the common ground with the Writer (capital W). As Atwood says, “writing has to do with darkness, and a desire or perhaps a compulsion to enter it, and, with luck, to illuminate it, and to bring something back out to the light”.