There are two common problems that academics face when it comes to writing. They are linked by one thing: time. It is one of the most important resources when it comes to writing. We need time to reflect on our research and to think about the best way communicate it to our audience. During some phases of your career, you will need to fit writing around a range of other commitments and may feel that you simply do not have time. At other times, particularly when faced with long periods of research leave, you will have the opposite problem, too much time, making it difficult to focus.

This post addresses that second question.

Writing when you have nothing to do but write!

So… You have a year to finish your monograph. Your teaching time has been bought out, your administrative roles have been re-assigned. Time seems to yawn ahead of you. Distractions are tempting as you feel the need to fill your time to feel busy and productive.

Here are five steps to think about:

- Choose to start

- Choose an approach that will get the best out of you

- Understand your project and plan

- Seek inspiration, not distraction

- Write regularly, write smart

Choose to start

… because, you know that old adage that ‘if you don’t choose a path, then someone will choose it for you’.

I’ve known a number of people start an entire year of writing with a wonderful sense of freedom, but then fail to deliver the promised monograph or research bid… or anything, in fact. The reasons that they give often boil down to the fact that they didn’t actually ‘choose’ to write.

In my book, choosing to write is OK, and choosing not to write is OK. Both are empowering, in different ways.

What’s less empowering is not making a choice – because that’s still, really, making a choice. Just not one that we own.

If we want to write, we have to choose to start.

Choose an approach that will get the best out of you

Take time to plan. Having chosen to start, simply piling into writing might be the worst thing that you can do. You have time – loads of time. So take time to plan, to think, to experiment, to reflect, to change your approach and try again. If you find your best approach and rhythm, you’ll get a lot more done, and better, and with better mental health, than simply putting fingers to keys and seeing what comes out.

Be self-aware. Think about how and when you have worked at your best in the past. Do you write slowly and methodically, or do you take the Jack Kerouac route? Do you need human interaction to develop your ideas? Do you need seclusion for long periods of time? Do you need to move your writing space regularly? Do you need noise or quiet? Different people need different environments to produce their best writing. Work out who you are as a writer and arrange your time and space to fit your best habits (not your worst!).

Understand your project, and plan

Bring together all the tasks you need to do to achieve your project(s). You’ll almost certainly have background reading, data organisation and choice, structuring at different scales, writing (in chunks), proofing, image selection, correspondence, bibliographies etc. When do they need to be done by? What else is there that needs to be fitted in? Conferences, travel, training, being ill? Family birthdays, housework and improvements? Christmas shopping? (it’s a whole year remember, and anything that you can plan-in is planned and won’t hijack your timetable).

Break your writing into segments. Like eating an elephant, one person I know got so much stress from trying to work out how to write their PhD ‘as a whole’, that they were on anti-depressants and only days away from giving up. And then they realised that if they wrote just 500 words a day, they’d produce a chapter every 6 weeks, and the full thesis would write itself in about 9 months. Then it just became a question of hitting a very achievable daily target.

Prioritise and allocate time. Make a list of all the writing, the tasks, the deadlines and put them in order. Make sure all your objectives have an appropriate list of tasks to get them done – is there anything missing from your list? Then allocate time to each task. And be generous.

Be kind to yourself. And, if you miss a deadline, be kind to yourself and reschedule. In many ways, that’s the advantage of planning. If you miss one target, you can see it in the context of the whole (which is planned) and don’t feel like the entire project has gone off the rails.

Seek inspiration, not distraction

Allow yourself to seek inspiration. Distraction [Dis-traction – or being ‘pulled away from’] prevents you from concentrating on a task. Inspiration [literally ‘breathing into’] feeds ideas into your task and transforms it. A key difference between the two seems to be the mental state that each puts you in. Distraction is about mental agitation, which prevents you from focusing on anything. Inspiration comes from deep focus – even if that focus isn’t your work. I’ve had some of my most inspired moments pruning fruit bushes in the garden!

Be in the moment, rather than being ‘always in the writing’. If you’re working to a plan, then this should be possible. If you’re on holiday, be on holiday – don’t be thinking all the time ‘I should be writing’. If you go to a conference, then ‘be there’. If you’re ill, then ‘get better’. If you’re reading, then ‘read’. Being always in the writing is – again – a state of mental distraction. Be where you are, and enjoy – knowing that the bigger project is planned, and still safely on the rails.

Write regularly, write smart

You’re looking to make all your writing time count. So these all bear repeating:

Once you have planned your writing project, then half and full days are best. Start each writing session by planning what you are going to do that session – don’t just start writing! It’s not always possible to write every day but write regularly, even in your research phase, to keep in practice and keep improving. Book onto our Regular, Productive Writing workshop to learn more about getting into good writing habits.

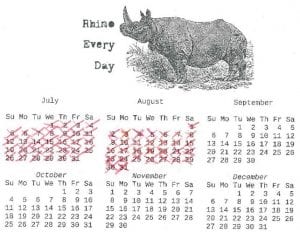

Or try the Seinfeld method known as ‘don’t break the chain’. Make a cross on your calendar every day when you write something – even if it isn’t much – some days it will be just enough to open up a new idea. Most of all, the visual cue of the calendar can help motivate you to make sure you write a little every day – just don’t break the chain:

- Plan each writing session. Think about how much writing you can manage in the time you have – write a few sentences specifying what content you will cover and how that will fit into the larger structure of the piece you are working on (if appropriate). This gives you focus for the day and stops you from getting distracted by your larger project.

- Eliminate distractions. Turn off your e-mail, switch off social media, put your phone on mute. Try to ignore that itchy feeling. It’s easy to distract yourself when things get hard. Enjoy a deeper focus without distractions.

- Write with others. By agreeing writing time with others, it’s easier to feel compelled to use it properly. Invite a colleague or a small group of colleagues to write with you. Agree a place and a time and commit to being there. Attend one of our writers’ retreats to try a great structured approach to writing regularly and together.

- Take breaks. For every 1.5 hours you write, you should take a ½ hour break. Your brain needs time to rest properly and regularly when you are working it hard. Most of us don’t take breaks because we are afraid of losing our train of thought or momentum, but it can be very damaging. A practical solution to this is to write a short summary of what you’ve written so far and what you want to tackle next before taking a break to help your brain rest properly and to help you get going again as quickly as possible.

- Find the right place. If you find you are interrupted too much in your office, write somewhere else. Or simply lock the door and unplug the phone during your writing periods – let the world back in for breaks and non-writing days.

Three things to read if you want to know more:

- Cal Newport, Deep Work. Rules for Focused Success in a Distracted World (London: Piatkus, 2016)

- Rowena Murray and Mary Newton, ‘Writing retreat as structured intervention: margin or mainstream?’, Higher Education Research & Development 28:5 (October 2009) 541-554

- Maggie Berg, The Slow Professor: Challenging the Culture of Speed in the Academy (Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 2016)